Beginning of the End(ometriosis)

Researchers have linked a bacterial infection with endometriosis development, opening up new avenues for treatment

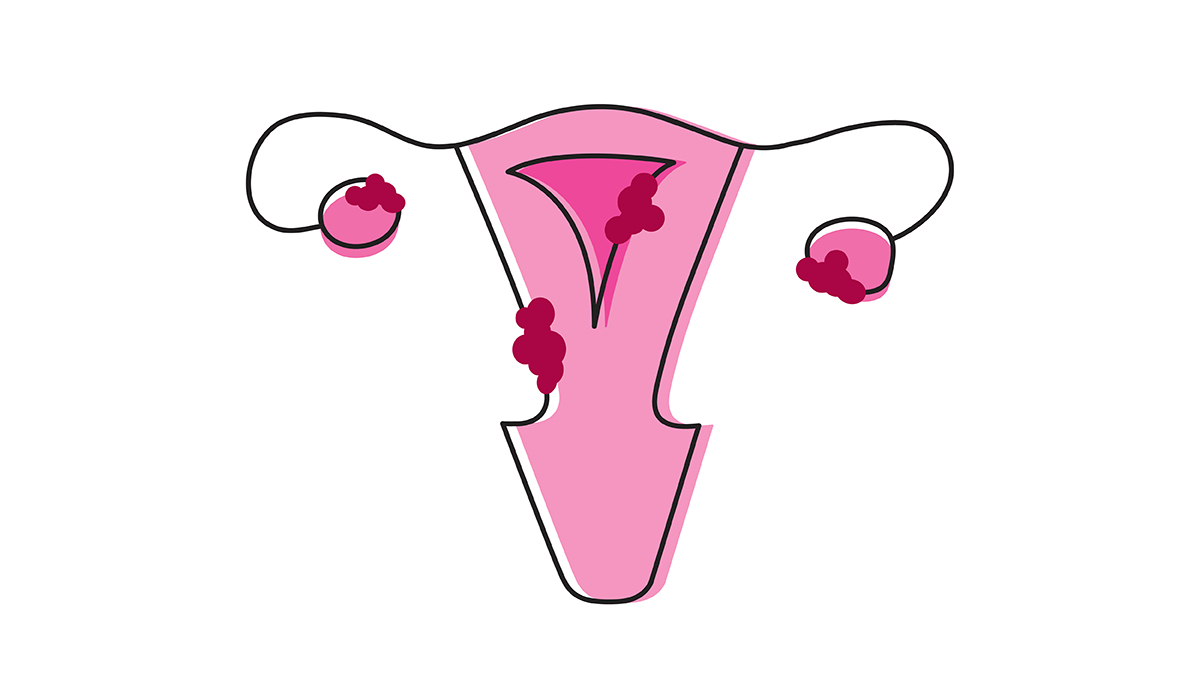

Endometriosis causes debilitating pain for millions of women of reproductive age worldwide – with no cure in sight. And because symptoms resemble other conditions – and women’s painful symptoms have become normalized in society and medicine – most women wait up to eight years to receive a diagnosis. The general consensus is that retrograde menstruation (see box) causes endometriosis; however, not all women who go through retrograde menstruation go on to develop endometriosis, indicating a missing piece to the puzzle.

Retrograde Menstruation

During menstruation, the lining of the uterus – the endometrium – sheds and is expelled as menstrual blood. In retrograde menstruation, this blood flows in the wrong direction, moving through the fallopian tubes and into the pelvic cavity instead of leaving the body through the vagina.

In a study from Japan, researchers found that Fusobacterium infection of the endometrium may contribute to the development of endometriosis (1). Senior researcher Yukata Kondo explains, “We showed that Fusobacterium infection of the endometrial cells resulted in activated transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling, causing quiescent fibroblasts to transition to Transgelin (TAGLN)-positive myofibroblasts (active fibroblasts), which gained the ability to proliferate, adhere to surfaces, and migrate.” Kondo says these events then contributed to the formation of endometriosis, which is the growth of endometrial tissue outside the uterus, usually in the pelvic area.

The findings are promising, but Kondo’s team was relying on an imperfect mouse model; mice do not naturally menstruate nor develop spontaneous endometriosis. “Endometriotic lesions in our mouse model therefore had to be induced by peritoneal injection of minced endometrial tissue,” explains Kondo, who also highlights that previous research using the same model has found important features of human disease, including the hormonal resistance of endometriosis.

Though there is no conclusive answer as to whether the bacterium plays a causal role in endometriosis, the results suggest its contribution to pathogenesis, which could open up new avenues for treatment. Right now, surgery or hormonal therapy are the only options available for endometriosis patients; however, there is a high recurrence rate after surgery and hormonal therapy can cause adverse effects. “We believe our data reveal a novel pathogenic mechanism of endometriosis involving Fusobacterium infection, making antibiotics an attractive option for eradicating the bacteria and treating the disease,” says Kondo. Indeed, the team is now working on a clinical trial of antibiotic treatment in a large cohort of endometriosis patients.

Reference

- A Muraoka et al., “Fusobacterium infection facilitates the development of endometriosis through the phenotypic transition of endometrial fibroblasts,” Sci Transl Med, 15, eadd1531 (2023). PMID: 37315109.