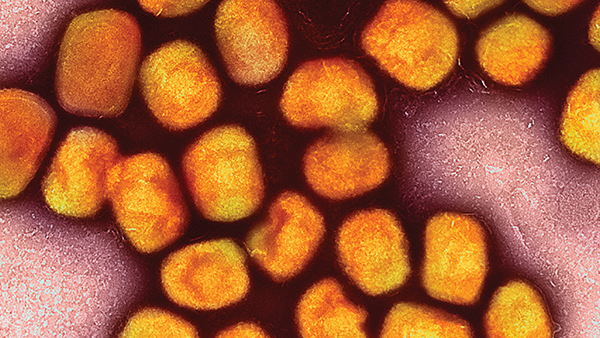

Is Measles Making a Comeback?

How a decline in MMR vaccination uptake in recent years is driving a rise in rubeola cases in the US

Measles spreads through the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes and is highly contagious – spreading even before the typical rash is seen. Everyone who is not immunized against measles or has not previously contracted the disease is at risk. However, unvaccinated, young children are at the highest risk of measles and its severe complications, including encephalitis and death. Though some people think that measles only consists of a mild rash and fever that clears up on its own, this is untrue. About 20 percent of people who contract measles will be hospitalized; one in every 1000 cases will develop brain swelling; and 1–3 in every 1000 cases will die.

Measles can also cause significant immunosuppression by suppressing lymphocyte proliferation, which can result in autoimmune diseases and a diminution of immune features such as skin reactions to tuberculosis. Death from secondary infections may then occur due to this immunosuppression.

The best way to protect yourself and others? Get vaccinated. The measles vaccine is given as part of a three-component vaccine that covers measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR). It is a weakened – live-attenuated – virus that causes mild infection so that, when the immunized individual is later exposed to the virus, the immune system produces antibodies to prevent disease. It takes a few weeks to be fully effective, but one dose is approximately 93 percent effective, and two doses are 97 percent effective in preventing measles.

In recent years, we have witnessed a decline in MMR vaccination uptake. Data published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revealed that, during the 2021–2022 school year, vaccination coverage among US children in kindergarten decreased to approximately 93 percent for all state-required vaccines (1) – a one percent decrease from the 2020–2021 school year. The vaccine exemption rate remained low at 2.6 percent; however, an additional 4.4 percent without an exemption were not up-to-date with the MMR vaccine.

Historically, certain communities have chosen not to be vaccinated, such as those with religious objections, either to medical intervention itself or vaccinations specifically. However, the recent decline in childhood vaccinations appears to be driven by families isolating themselves during the COVID-19 pandemic or skepticism, with some parents believing the vaccines are either not helpful or perhaps harmful. Indeed, there are a number of common misconceptions and concerns surrounding the MMR vaccine. For the record, the vaccine does not cause measles. Nor does the vaccine or any of its components cause autism; the fraudulent research from the 1990s has been researched thoroughly, and the claim has been refuted. Unfortunately, changing people’s beliefs is easier said than done. Furthermore, although the vaccine can cause a fever and occasionally fevers can cause seizures, febrile seizures following MMR vaccination are rare and are not associated with any long-term effects.

On the Rise

When I was in medical school many years ago, I never once saw a case of measles. In 2000, endemic measles had officially been eradicated in the US; there were no longer significant numbers of cases, only occasional ones here or there. But I saw many cases when I practiced in Texas in the early 1990s, and I have seen or learned about many more throughout my career. There are now routinely small to large outbreaks in schools – and cases are on the rise (2). If the US does not effectively address the decline in MMR vaccinations and other vaccine-preventable diseases, they will make a comeback.

Measles occurs in most countries in the world, but in countries without vaccine programs, measles epidemics occur every two to five years. Globally, measles causes 36 cases per 1 million persons each year and around 134,200 deaths annually (3). At times, measles is brought into the US by unvaccinated travelers who acquire the disease while abroad, bring it into the country, and spread it to others. According to the CDC, measles is one of the most contagious diseases known, so it spreads rapidly among people who are not immune.

The most recent large outbreak in the US was in Ohio in 2022. According to Columbus Public Health, the outbreak consisted of 85 cases, 36 hospitalizations, and no deaths. All cases were under 17 years old, and only four were partially vaccinated. The remaining cases consisted of unvaccinated individuals and one of unknown vaccination status (4). The outbreak occurred when four children at a childcare facility came down with the virus and spread it to unvaccinated and partially vaccinated members of their community (4).

To contain the outbreak, local health officials “sounded the alarm” by being transparent about the state of the outbreak, informing the public about the virus and how easily it can spread, and promoting the importance of getting young children vaccinated against it (5). Members of the CDC were also called in to assist with contact tracing.

Public health departments have tried to alleviate concerns nationwide via education campaigns – addressing the concerns of parents in particular. They have also tried to make vaccines – including MMR – more available by designing back-to-school campaigns and opening vaccine clinics prior to school opening and in underserved communities. Most state laws require children to be fully vaccinated, and health departments work with school administrators to ensure vaccines are available to allow children to attend school. Rural and frontier communities still lack sufficient access, so there is still work to be done to get vaccines into these areas and improve coverage across the country. Only then might we see measles cases begin to simmer down once more.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Vaccination Coverage with Selected Vaccines and Exemption Rates Among Children in Kindergarten — United States, 2021–22 School Year,” (2023). Available at: bit.ly/3P7K13k.

AD Mathis et al., “Maintenance of Measles Elimination Status in the United States for 20 Years Despite Increasing Challenges,” Clin Infect Dis, 75, 416 (2022). PMID: 34849648.

World Health Organization, “Measles,” (2023). Available at: bit.ly/3NQa3qx.

The City of Columbus, “Measles Public Report,” (2023). Available at: bit.ly/me45g.

Howard, Jacqueline, “Measles Outbreak in Central Ohio Ends after 85 Cases, All among Children Who Weren’t Fully Vaccinated,” CNN, (2023). Available at: bit.ly/445oH2K.

Shuda, Nathaniel, “Columbus-Area Measles Outbreak Was the Nation’s Largest in 2022. What about Now?,” The Columbus Dispatch, (2023). Available at: bit.ly/3XtrhgI.