Feeling the Selective Pressure

Key genetic differences may have determined who survived the Black Death pandemic – and how our immune system respond to diseases today

Infectious diseases have placed intense selective pressure on the human and animal population throughout history, with many of these involving immune response genes. The problem, however, lies with linking cause and effect – which pathogens caused specific adaptations?

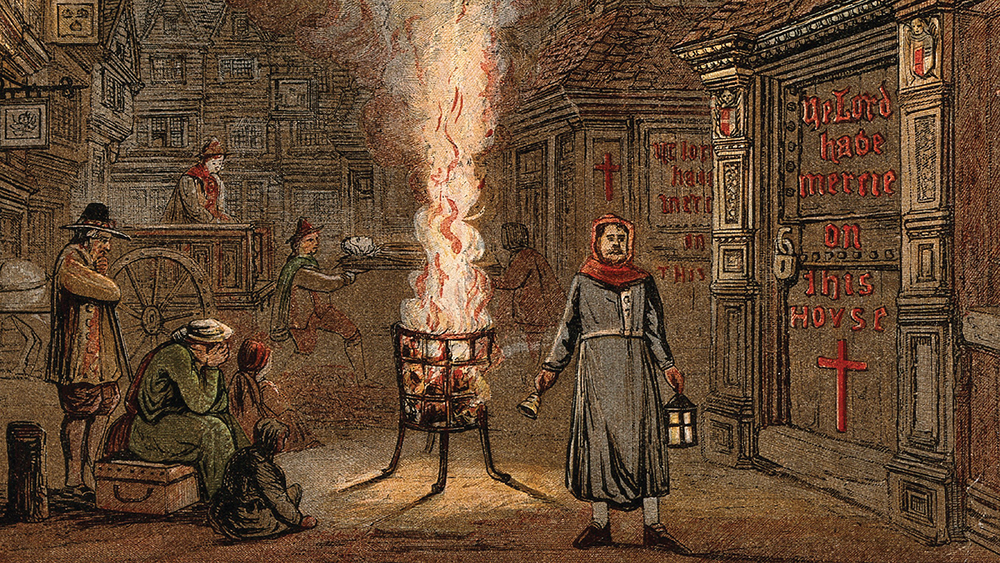

In the mid-14th century, the Black Death wiped out up to 50 percent of the global population – cementing its place as one of the deadliest pandemics recorded in modern history. In an effort to understand whether Yersinia pestis – the bacterium responsible for the second plague pandemic – triggered a case of natural selection, researchers have analyzed the DNA of victims and survivors who lived in Denmark or London before, during, or after the Black Death (1). By their reasoning, variants associated with susceptibility or protection should display opposite frequency patterns across the sampled timepoints; variants conferring increased susceptibility should be high in frequency in individuals who died during the Black Death then decrease in post-pandemic survivors or descendents, whereas variants associated with protection should rise after the Black Death.

By tracking genetic variants that became more common throughout the pandemic, they found key genetic differences associated with plague protection or susceptibility. In particular, changes in ERAP2 allele frequencies were implicated; people with two identical copies of the protective ERAP2 allele were about 40 percent more likely to survive the pandemic than individuals homozygous for the deleterious variant. This allele is linked with increased ERAP2 expression and production of the canonical, full-length protein ERAP2, which the researchers suggest is associated with an increase in Yersinia-derived antigens to CD8+ T cells. They also found that macrophages from individuals with the protective allele yield a unique cytokine response to infection and better limit replication in vitro.

After the Black Death, plague outbreaks continued to occur in waves up until the mid-19th century, but these often wreaked less havoc than their predecessors. Why? Possible explanations span changing health, sanitation, and cultural practices, but it could also be that, because more people with protective variants survived the Black Death, their descendents will have inherited the survival advantage and been protected against future waves of the bubonic plague.

Fast-forward to modern day, and the research demonstrates how historical natural selection can impact current susceptibility to chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. When stimulated with a range of pathogens, ERAP2 was transcriptionally responsive and demonstrated its key role in immune response regulation – suggesting that the selective pressure from Y. pestis likely impacts immune response to other pathogens or diseases. The paper cites that the advantageous ERAP2 variant against Y. pestis is actually a known risk factor for Crohn’s disease and some communicable diseases. Perhaps the ERAP2 variant protected our ancestors through the Black Plague, but this may have come at a trade-off for immune disorders in the present day – or “a long-term signature of balancing selection,” as the researchers state.

References

- J Klunk et al., “Evolution of immune genes is associated with the Black Death,” Nature, 611, 312 (2022). PMID: 36261521.