Where Are the Antifungal Vaccines?

Developing vaccines for fungal diseases is a multifaceted challenge that demands a multifaceted solution

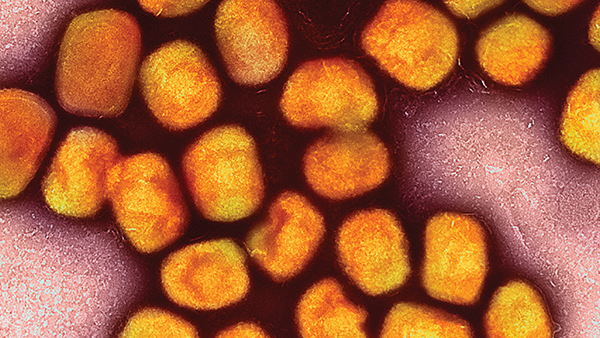

It’s true that fungi don’t seem to get as much attention as viruses, bacteria, and other infectious pathogens – why? Serious fungal infections (mycoses) occur mostly in persons who are immunocompromised; in contrast, many viruses, bacteria, and parasites are primary pathogens that can infect and kill people with intact immune systems.

If you think back 100 years ago, lethal fungal infections were rare because there weren’t many immunocompromised patients – but that’s no longer our reality. Tens of millions of people worldwide live with HIV/AIDS. People with solid organ transplants need immunosuppressive medications to prevent rejection. Cancer chemotherapy can lead to profound immunosuppression. Corticosteroids and other biologics are commonly used to treat diseases characterized by excessive inflammation, such as autoimmune diseases. As a result, the at-risk population has skyrocketed – worldwide, an estimated 1.5 million people a year die from fungal infections. Recognition from medical professionals and the public of the importance of tackling fungal infections is slowly increasing, but challenges still remain.

One of the problems encountered with fungal diseases is that there are currently no clinically approved antifungal vaccines. But there are dozens of fungal vaccines in development. We can categorize fungal vaccines by the pathogen(s) they are directed against. Some vaccines in development aim to protect against multiple pathogens by targeting components shared by most medically important fungi; one such component is β-D-glucan, which is found on fungal cell walls. Others seek to protect against a single fungal disease, such as coccidioidomycosis.

We can also categorize fungal vaccines by their general composition. For example, some vaccines are composed of whole organisms that are attenuated or killed, while others are made from crude extracts or defined antigens. Some subunit vaccines take advantage of RNA technology akin to what is used in COVID-19 vaccines.

Multifaceted challenges

The lack of fungal vaccines can be broken down into two distinct challenges: scientific and logistical. On the scientific side, fungi are complex pathogens with a large genome; identification of immunoprotective antigens in an organism that expresses over 5,000 proteins is not trivial. Whole-organism vaccines run the risk of triggering autoimmunity because fungi and humans are eukaryotic and, as such, share many cellular features. Host defenses against many medically important fungi rely primarily on T cell immunity, but T cell vaccines are challenging to develop, partly because approved vaccine adjuvants mostly stimulate antibody responses. In addition, responses to T cell vaccines can be heterogeneous because of the many HLA alleles in the human population. But perhaps the biggest scientific challenge is developing vaccines that are potent enough to stimulate robust responses in immunocompromised individuals.

Perhaps the least challenging fungus targeted in vaccine development is Coccidioides species. This fungus causes coccidioidomycosis – an endemic mycosis that often afflicts those with apparently intact immune systems. The incidence is high enough that efficacy trials are feasible and immunocompetent subjects could be enrolled – but unfortunately that’s not the case with most other fungi. Each fungus presents unique challenges with vaccine development. Fungi that rarely cause infection are challenging because clinical vaccine trials need to enroll large numbers of subjects to evaluate efficacy. Fungi that predominantly infect severely immunocompromised persons are challenging because of the uncertainty surrounding whether one can elicit an adequate immune response.

When it comes to logistics, vaccine trials are very expensive. Pharmaceutical companies have not shown strong interest in supporting fungal vaccines. In addition to the scientific hurdles, for many vaccines they do not see a pathway to profits because most people who would benefit reside in resource-poor countries.

Overcoming hurdles

To overcome the challenges presented by antifungal vaccine development, strategies must be developed and individualized according to: i) the vaccine and ii) the target population. A vaccine designed for an immunosuppressed population could be administered prior to anticipated immunosuppression; for example, before an anticipated organ transplantation. Using newer adjuvants that elicit strong T cell responses to vaccine antigens should be considered for vaccines against fungi. Autoimmunity risk can be minimized by targeting molecules with no homologies to human cells. And finally, scientists must form partnerships with pharmaceutical companies, governmental agencies, and non-government organizations to bring promising vaccines to clinical trials.

Recent significant breakthroughs make me hopeful of a future filled with antifungal vaccines. For example, new adjuvants that promote strong antibody and T cell responses to fungal proteins have had very promising results in rodent studies, and dogs were protected in a trial of a live-attenuated Coccidioides vaccine. Also, a vaccine to prevent recurrences of vulvovaginal candidiasis was successfully tested in women – demonstrating the feasibility of human fungal vaccine trials.

The World Health Organization has significant influence worldwide, so when it published its fungal priority pathogens list in 2022, it brought much-needed attention to the importance of fungal diseases. This need extends beyond vaccines; there is also an urgent need for better diagnostics, therapeutics, and prevention measures – and we need to make the already existing measures available to all who need it. Many countries cannot afford first-line antifungal drugs and simple diagnostic tests, such as fungal cultures, are not readily available.

I’m optimistic that the increased awareness of the need for fungal vaccines will direct more resources towards development. But – reflecting on my point above – when vaccines do find their way through approvals, they need to be made available to the whole globe and especially the populations most in need.