When Pandemics Collide

One pandemic is enough to face, but what happens when another gets thrown into the mix?

Almost 42 years since the first cases of HIV/AIDS were reported in the US, it continues to be a global public health issue; however, thanks to many advancements in the field, most people living with HIV (PLWH) are able to lead long, healthy lives. But what happens when another pandemic crops up and gets thrown into the mix? When COVID-19 darkened our doors, it didn’t mean that other communicable diseases were happy to put their “lives” on hold. No – other pathogens of pandemic (or epidemic) proportions still required attention, as did the people living with them.

In October 2022, I had the pleasure of attending HIV Glasgow, where many of the speakers discussed how PLWH have been displaced or how services have been disrupted because of current events, conflicts, and disasters. Of these, COVID-19 was a frequent topic of conversation. Casper Rokx – an internist and HIV/infectious diseases specialist at the Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands – explained the idea of pandemic–pandemic interaction (PPI) – that is, the influence that two pandemics have on each other. I caught up with Rokx after the conference to delve a little deeper…

“The emerging pandemic can be considered as a perpetrator on the care cascade of affected individuals by the already existing pandemic,” explains Rokx. “This can be due to reallocation of human resources, care, or funding towards confronting the new threat, or due to an increased burden of disease in those affected by two pandemics.”

To assess the impact of a new pandemic on patients living with illness from another, Rokx tells me that seven aspects are taken into account: diagnostic facilities; susceptibility to the new disease; responsiveness of preventative measures; disease severity; transmissibility; treatment response; and genetics. The impact of a new pandemic is associated with how many of – and how much – these aspects are negatively affected. Next, factor in the stigma surrounding certain diseases and the healthcare capabilities of different countries, and we can determine the level of support that those affected by the two pandemics will receive.

HIV services worldwide have been significantly disrupted since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and we can apply the PPI concept to these colliding pandemics. “The number of HIV tests have reduced dramatically, linkage to care was made harder because people were not allowed to enter hospitals, and antiretroviral therapy was less monitored. Telemedicine has been a good addition, but it is impossible to do a physical examination,” Rokx highlights. “We do not have yet strong evidence that major outbreaks or emerging resistance have occurred due to less monitoring, but this would only become apparent in due time given the relatively long time that HIV can go unnoticed in a population.”

One more in the mix

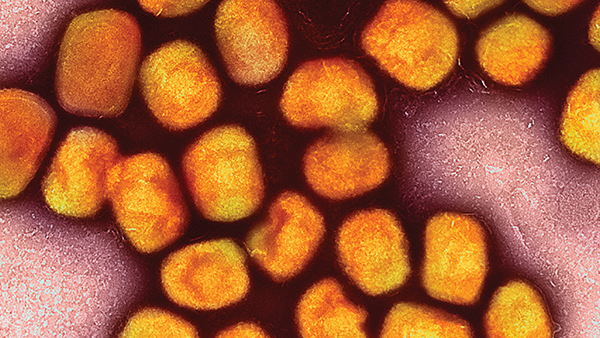

Humanity was awash with emerging outbreaks throughout 2022 – from acute hepatitis of unknown cause making the rounds in young children in Europe to the Sudan ebolavirus outbreak in Uganda. In May 2022, mpox arrived on the shores of non-endemic countries, having mostly been limited to Central and Western Africa until then. It quickly became apparent that the outbreak was disproportionately affecting men who have sex with men (MSM) and messaging was targeted to at-risk groups – careful to avoid repeating the history of stigma against MSM and the LGBTQ+ community.

Mpox may have affected HIV services, but not in the same way as COVID-19 – in fact, perhaps the opposite. Rokx tells me, “[HIV and mpox] might have been augmented because STI testing clinics tasked with diagnosing mpox received more support. The issue with mpox was that HIV testing should have been done more often; with one-third of the people with mpox having an HIV infection, it became clear that mpox is an HIV indicator condition and warrants universal testing upon diagnosis.”

The changing conversation

Before COVID-19, media outlets didn’t seem to report on emerging outbreaks or new discoveries in the ID space as much as they do now. Certainly, they used to cover the big topics – MERS, SARS, Ebola, and Avian flu outbreaks – but there seems to have been a shift in public awareness campaigns and reporting. Or perhaps members of the general public are simply more aware or even hyper-alert to messaging. Rokx actually highlights a benefit to this from the scientific side. “What has changed due to COVID-19 is that more attention goes to tackling new pandemics early on,” he says. “I believe this facilitated a timely response to mpox and increased attention on it at HIV services due to its relation [as an indicator condition] – thereby maybe helping HIV services too.”

When asked whether anything could have been done to mitigate the impact of an emerging pandemic on HIV services, Rokx mentions that the HIV community has tried to gather as much evidence on the consequences and risks of COVID-19 on people living with HIV so they know what to focus on for the next emerging pandemic. “I believe the best mitigation strategy is to continue supporting pandemic surveillance systems for new pathogens with pandemic potential and fostering broad international collaboration within the HIV community to tackle questions surrounding early diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis – not only in specific countries, but in all relevant settings and key populations.”

To make HIV services more robust against emerging and re-emerging threats in future, Rokx says that clinicians and policymakers must “be prepared, have manpower and financial support, collaborate, and use models such as PPI to systematically evaluate the potential and actual impact of pandemics on PLWH.” However, there are low- and middle-income countries that still don’t receive the resources required to mitigate this impact – and Rokx leaves me with this reminder. “Global equity in pandemic responses is critical for decreasing the impact on as many people with HIV as possible.”