Transmission Time Machine: Consumptive Chic

How tuberculosis influenced fashion and beauty standards in the Victorian era

Fashion and beauty standards through the decades – and centuries – have fluctuated significantly, but did you know that tuberculosis (TB) once played a role in these societal ideals?

TB symptoms include coughing up blood, weight loss, fatigue, and fever – and, if not treated properly, patients face a poor prognosis. In the 1800s, very few survived the disease, and those who did suffered from severe recurrences that stole any chance of a normal life. Eventually, patients would die of what was then known as “consumption,” which made them deathly pale and thin, but with red lips and rosy cheeks.

The 19th century was marked by the opulent extravagance of Victorian fashion. For women, this meant tightly corseted waistlines and voluminous skirts, while men donned tailored suits, top hats, and well-groomed facial hair. But during this time, consumptive chic became the epitome of beauty.

Women began to embrace the consumptive aesthetic – they powdered their faces to achieve a ghostly pallor, applied rouge to their cheeks to mimic feverish flushes, and wore dresses that accentuated their frail frames. Tight corsets exaggerated their hollow waists and delicate collarbones, further accentuating this ideal of fragility.

Romanticism is one explanation for these ideals; dying of consumption was seen as a quiet, delicate way to die – robbing people of their youth. The romantic era celebrated the energy associated with youth, with many writers and artists of the time being young themselves. Famous artists and writers at the height of the period often portrayed consumption in a romantic light or wrote about the disease and its impact on their lives.

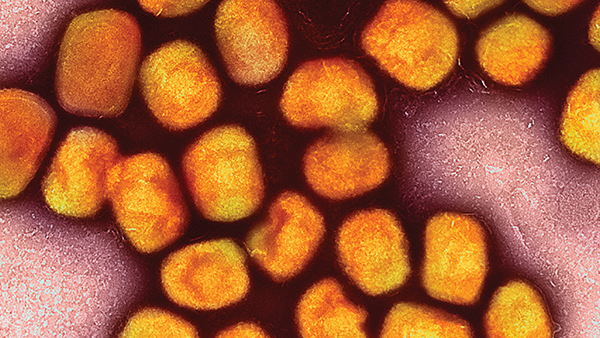

It wasn’t until 1882, when Robert Koch discovered that TB was caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the disease was contagious that these trends took a turn. As this knowledge spread, the romanticism of TB quickly waned, and fear of infection took hold. People became more cautious and beauty standards shifted away from the frail and emaciated look; instead, a robust, rosy complexion became the new beauty ideal, reflecting vitality and good health.

Understanding of hygiene and sanitary practices also started to improve. For example, with the realization that long, flowing skirts were sweeping germs up from the street and into the home and making people sick, skirts became shorter with no trains. Corsets and restrictive clothing also began to fall out of favor as women sought more practical and healthier options. Men’s beards and mustaches also came under fire for the potential to harbor dangerous bacteria and germs.

The relationship between TB and Victorian fashion reminds us how society’s perception of beauty can be influenced by unexpected sources – and how our understanding of infectious disease can drastically shape our behavior and our perception of the world around us.