The Key to Pandemic Prevention

A new roadmap showcases the importance of biodiversity in protecting public health

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers have pondered the possibilities of tracking future pandemics and preventing them. Enter Raina K. Plowright and team’s proposed roadmap for preventing the next pandemic. The focus? Protecting biodiversity to protect human health (1).

To learn more about this global, multidisciplinary project, we spoke with Manuel Ruiz-Aravena, Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Aquaculture at Mississippi State University, USA.

Why did biodiversity become the focal point of the study?

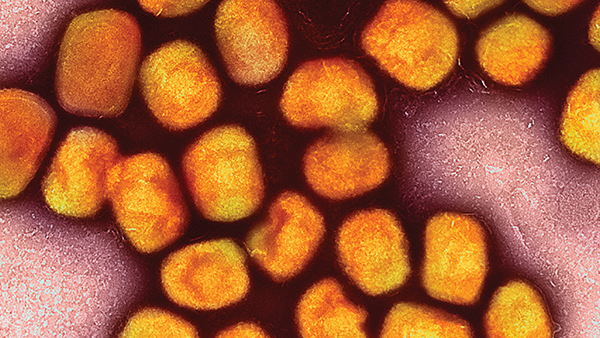

This study came into existence through a workshop organized by Plowright, where we discussed the relevance of bats carrying viruses with high consequences, such as SARS-CoV-2. A well understood history of bats and virus-carrying is the Hendra virus, which emerged in Australia in 1994 (2), transmitting from fruit bats, to horses, and then to people. Since 1994, Hendra has infected 7 people, with 4 of these ending in fatalities. After a long period of researchers studying why this virus emerged as a public health concern in recent decades, evidence points to an alignment with low-quality habitats and loss of critical habitats for bats during winter periods in Australia. Such loss of habitat security drives bats into agricultural areas in search of food and shelter.

This idea came to fruition in 2020 when the bushfires triggered a huge nutritional bottleneck for bats; further analysis showed that restoring ecological conditions could put a stop to the Hendra virus. In our workshop, we discussed whether this strategy could be used for other viruses. After all, this concern isn’t just present in Australia – it affects the whole world, from Ebola in Africa to the worldwide effects of SARS-CoV-2. And that is what led to the creation of a framework that incorporates land use induced spillover, identifying ecological interventions for disrupting these spillovers and stopping pandemics at the source. The overall idea was to develop a blueprint that can be applied in all communities to protect people, of course, with some variation depending on local conditions.

Can you tell us about the roadmap you created?

The main structure of the roadmap is based on three key points and actions to take: protect where bats roost, where they eat, and protect people at risk. The first two points reside in ensuring the habitat of the species is intact and protected to restore their health balance. Of course, there are areas with conflict of needs, where local communities using land resources can disturb these habitats. In these circumstances, there’s definitely a demand for more resources and support, which I hope will come in the following years. For now, we should focus on protecting species during critical periods, such as harsh winters.

There are also areas of the world where communities rely on wildlife habitats for a source of income. For example, Bracken Cave in San Antonio, Texas, is home to an estimated 20 million Mexican free-tailed bats and sees thousands of tourists every year. There’s no known risk in this area, but close interaction represents an interface of contact between humans and bats. Of course, there are positives to illustrate these activities, but we can still take steps to make them safer. For example, we know horseshoe bats in Asia carry SARS-related coronavirus in areas where guano mining might take place and commonly there’s no personal protective equipment provided to protect communities from potential infections. Another key element in preventing future outbreaks lies in education. If you’re unaware of the risks, you won’t have the tools to protect yourself and your community.

Another key point in our roadmap is to secure response. This includes detecting outbreaks and conducting community testing to identify infections that don’t trigger an outbreak.

Overall, reaffirming ecological principles across bat species and international contexts in policy and actionable recommendations is incredibly satisfying. Putting all the pieces together from different systems told us that our blueprint works and is likely to be applicable in various communities.

What do these findings mean for the future of pandemic prevention?

Our roadmap shows areas of intervention for any discipline and any level of organization – from small communities and rural villages to country-wide and international interventions. Seeing the problem in different ways is allowing us to find solutions that we were previously blind to. This is also evident in other research initiatives. There is a constantly growing evidence base that managing local areas is the key to protecting and serving the community.

What’s next for this research?

The evidence shows that by understanding the ecology of wildlife species and how that affects their health is crucial to protecting public health. Across the team, we will continue developing the science for ecological interventions that can help protect human health through sustainable actions. These actions also have the benefit of helping mitigate other pressing issues such as species extinctions and climate change. It is a win on all fronts.

I think we’re in a moment in history where one health is transitioning from being a mostly academic term into a discipline, which opens a plethora of exciting opportunities not just in pandemic prevention, but also in diagnostics and public health in general.

References

RK Plowright et al., 15, 2577 (2024). PMID: 38531842.

WHO (2024). Available at: www.who.int/health-topics/hendra-virus-disease#tab=tab_1.