You are viewing 1 of your 3 articles before login/registration is required

Preempting Polio

Following the detection of positive poliovirus samples in London sewage, should the UK consider introducing the novel oral polio vaccine?

The year 1984 marked the last case of polio in the UK.

Almost 40 years later, the detection of positive poliovirus type 2 (PV2) samples in London’s sewage network has caused understandable concern. Testing was quickly rolled out across the UK, including both major cities and smaller towns. In September 2022, the UK’s Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) advised targeted polio booster doses for all children aged between one and nine years old in all London boroughs.

These booster shots use the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV); however, if the surge in positive polio samples results in actual confirmed cases, we might need to consider using the novel oral polio vaccine (nOPV) as well as increased testing to combat the spread of the virus. Why? The UK’s current IPV vaccine was introduced in 2004 – one year after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that polio had been eradicated in its European region. IPV provides excellent protection from severe disease; however, it is possible to be fully vaccinated and protected from the worst of polio, but still acquire the virus asymptomatically and spread it to others. In other words, IPV alone may not be entirely sufficient to avoid an outbreak, if new cases do occur.

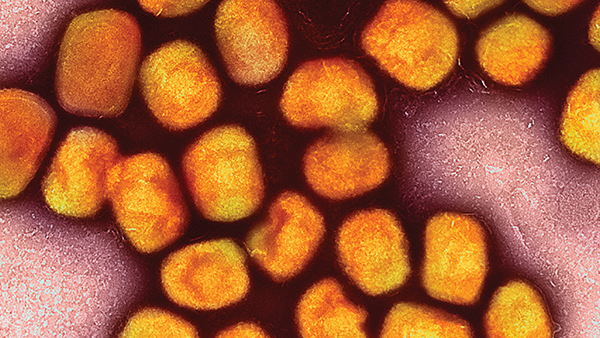

Following the discovery of vaccine-like PV2 isolates in London Beckton sewage samples in February 2022, the virus has since evolved and, by the end of May, it met the criteria of a vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV2). Vaccine-derived poliomyelitis virus (VDPV) is caused by the oral polio vaccines still used in many developing countries because they are simple to administer and less expensive than IPV. On rare occasions, if a population is under-immunized, the virus can transform into pathogenic strains, known as VDPV. VDPVs behave more like the wild-type virus, can sustain outbreaks, and occasionally leads to paralysis in unvaccinated individuals.

Health officials suspect that a person entered the UK from a country that still uses a traditional oral polio vaccine (OPV), but the PV2 levels still being detected in late September – and the high genetic diversity among these samples – suggest that, although the cases are genetically related, virus transmission is now taking place in separate networks of individuals across several London boroughs and possibly surrounding areas (1). This pattern is not consistent with virus shedding by only one or a few individuals. The UK’s Health Security Agency has been in close contact with the WHO and the Global Polio Eradication Initiative and it has now been formally confirmed that the UK has a circulating VDPV2 virus (1).

First, I believe we should consider increasing testing and introducing the nOPV vaccine to bolster the UK’s defenses. The WHO considers the latest nOPV2 to be inexpensive and easy to administer. It produces a gut reaction that protects the individual from disease and stops transmission by using a more stable version of OPV, which means the virus is much less likely to mutate.

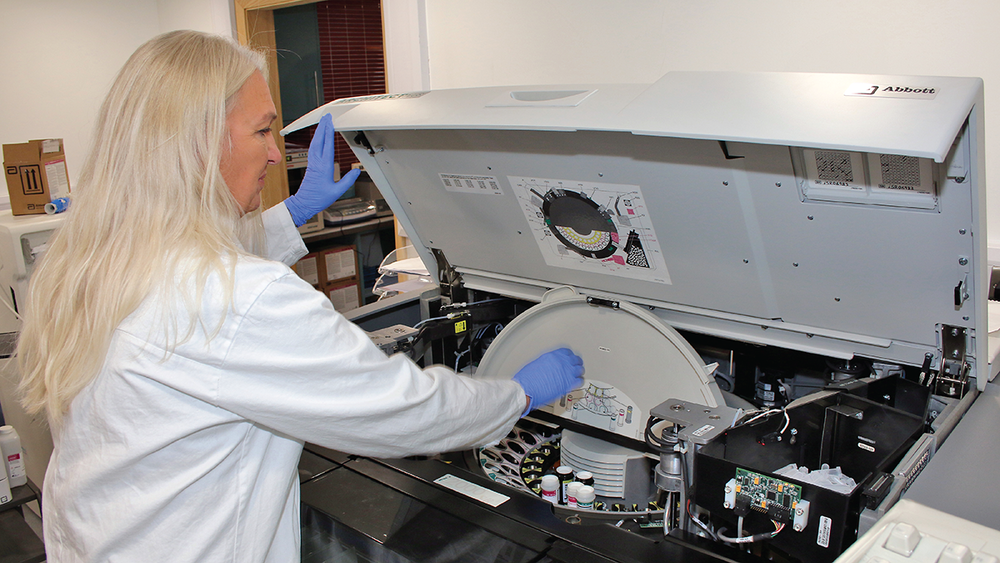

Second, I believe the UK government should consider introducing polio antibody testing in areas where samples have been found in sewage – despite the lack of confirmed cases so far. Virus testing is usually performed using stool samples or antibody testing, but the latter requires only a simple blood test to establish whether a person has successfully developed antibodies after vaccination or still retains the antibodies from their childhood vaccinations. Though it’s true that these tests are currently expensive, that’s because, until now, they have rarely been required.

So far, the poliovirus samples found in London’s wastewater have not been linked to other regions of the UK; however, they have been linked to cases found in the US and Israel (1,2). A recent opinion piece in the British Medical Journal has called for the potential use of nOPV in America as a “Plan B,” should the virus spread there (3). Similarly, Britain cannot afford to be complacent in its battle to stop the return of this potentially lethal disease – by making the necessary preparations to implement widespread polio antibody testing and vaccination now, we have the opportunity to proactively respond to the threat.

Images credit: London Medical Laboratory.

References

- UK Health Security Agency, “Inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) booster campaign: information for healthcare practitioners” (2022). Available at: bit.ly/3Oti0AK.

- Global Polio Eradication Initiative, “Updated statement on report of polio detection in United States” (2022). Available at: bit.ly/3GC239j.

- N Schwalbe, JK Varma, “The US needs to prepare to introduce the novel oral polio vaccine,” BMJ, 379, o2388 (2022). PMID: 36195323.