James Phipps, We Salute You

It’s been 200 years since the death of Edward Jenner – but how best to celebrate his achievement?

The UK is celebrating the legacy of Edward Jenner with the release of a commemorative £2 coin (part of a new series of coins being released to mark the ascension of King Charles III to the throne). The coins, which range in price from £12 to £1,225, were designed by Henry Gray, and feature Jenner’s contribution to smallpox eradication on the “tails” side.

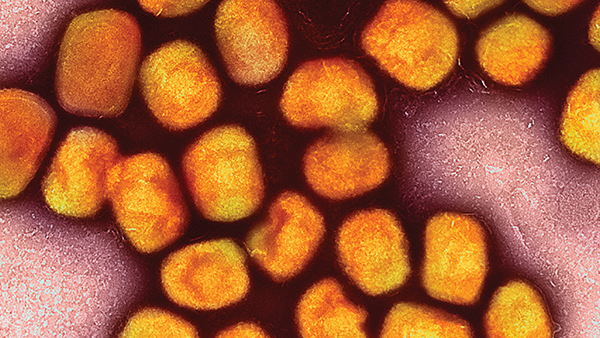

It’s been 200 years since Jenner’s death, so it seems fitting to look back on the (in)famous story of Jenner’s experimental cowpox vaccine. During a period when the obedience of children extended to the point of allowing their father’s employer to stab them in the arm with a lancet loaded with “matter” from a dairy maid’s cowpox blister, poor little James Phipps became the center of an experiment that would send a modern ethics committee into a real spin. (To be fair to Jenner, he had inoculated his own son against swinepox some years earlier, so he was likely confident of the procedure’s success.)

Personally, I would love to have listened in on the conversation between Jenner and Phipps’ father – if there even was one. How did Jenner persuade the father to give consent, if any was given at all? Did money exchange hands? I can only imagine the feelings of the trusting eight-year old being led into a makeshift clinic to find Jenner sharpening his implements…

There are two famous images depicting this scene. One, by Ernest Board from the early 20th century, depicts a kindly Jenner and a curious Phipps with sleeves rolled up, being gently held by a mysterious maternal figure. A very private image, Board’s depiction resembles hippocratic discretion and consideration. The doctor-patient relationship is evident – the boy bravely watching the lancet as it penetrates his skin. The second, a slightly earlier Gaston Mélingue lithograph, is more disturbing; it shows a reluctant, frightened Phipps being held down, outdoors, by an indistinguishable chap (Phipps Senior?) and a darker, more determined Jenner. Various members of the household look on with fascination – while the dairy maid (I guess given the inclusion of a yoke and bucket) appears to bandage her freshly scraped cowpox blister.

The conduct of Jenner was questioned at the time, but we should not underestimate the courage of children any more than we should the ingenuity of researchers from two centuries ago. It would have been pointless – even impossible – for Jenner to have performed his experiments on rodents first, and while it seems unfair that the son of a poor man should have to step up and take on the role of guinea pig, it is fitting that what Jenner learned from Phipps helped achieve the world’s first (and currently only) eradication of a disease.

Mandatory smallpox vaccination became government policy in the UK as early as the 1840s, and, by the early 20th century, the disease existed only in small pockets in Europe. The first half of that century also saw a global cooperation as the fight against smallpox was taken to colonial areas, and, by the 1970s, smallpox had been eradicated in South America, Asia, and Africa. The WHO’s official global declaration of smallpox eradication came in May 1980.

James Phipps’ bravery and contribution was acknowledged and rewarded by Jenner with a lease-free cottage in which he could raise his small, smallpox-free family. One could argue that Phipps’ name and image should have been better etched into history, so that, 200 years later, the world would be saluting him just as much as Jenner.

This article originally appeared on our sister brand, The Medicine Maker.

![By Ernest Board - [2] images.wellcome.ac.uk, Public Domain. By Ernest Board - [2] images.wellcome.ac.uk, Public Domain.](https://d2twf77w0avz7h.cloudfront.net/AcuCustom/Sitename/DAM/002/0523-202-James-Phipps-Main2.png)