Adventure Science

Searching for the next zoonotic viruses

Scientists know a great deal about zoonotic diseases – sicknesses that move between animals and humans, such as rabies, West Nile virus, and Lyme disease. But the human race is still vulnerable to the next virus – and the next pandemic – because we don’t know enough. Six out of 10 infectious diseases, and three out of four emerging diseases, are zoonotic (1). We can avoid being caught unprepared by actively looking for them.

Due to population growth, the ease of global travel, and the human thirst for unique experiences, humans are invading areas previously inhabited exclusively by animals. The two groups are interacting in unprecedented ways – and exploring these interactions can help us understand the conditions that cause the sharing and spread of disease.

To gain information about new viruses and how to deal with them, we need a holistic approach that takes into account the fact that human health is connected to the health of animals, plants, and the environment. This kind of transdisciplinary approach isn’t new; it’s called One Health and it allows scientists, governments, and health agencies around the world to collaborate for the benefit of human health.

For example, if a lot of birds are dying of West Nile virus in Africa, local scientists who know the ecosystem should lead the research to understand the cause of the outbreak. The national government could provide funding and disseminate public health information while avian experts provide research support. Maybe a US lab with specialized equipment can cost-effectively process samples and share findings. All of this serves a common goal – to learn how to prevent the birds from getting West Nile virus so they don’t pass it onto other animals and then to us. By empowering scientists in local communities to research and ultimately contain a virus before it gets on a plane and travels to the other side of the world, everyone – human or animal – is safer.

Achieving optimal health outcomes requires us to move away from a reactive approach. For zoonotic diseases we’ve already studied, such as Lyme disease or West Nile virus, we have learned to identify symptoms in the infected animals, warning signs that indicate a person has been infected, and treatments. Both humans and animals are protected because we have done that work ahead of time – and we can make use of it rapidly when an outbreak hits.

The spread of COVID-19 taught us that we can rapidly develop vaccines, get them to the right places, and contain the spread of disease. But it also revealed a fundamental lack of information about the source of the disease and how it spread. We knew that coronaviruses could be a problem because of the SARS outbreak in 2003 and the rise of MERS some years later, and viral trials completed at the time might have allowed us to be more prepared for the arrival of SARS-CoV-2.

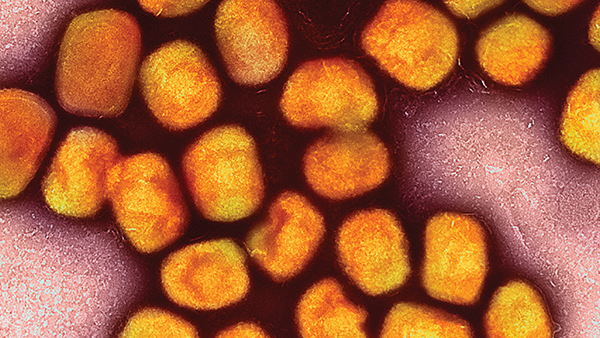

Lessons learned from a small outbreak of monkeypox in the United States in 2003 – the first report of the disease outside Africa – illustrate the need for a One Health approach in our interconnected world. Prairie dogs, purchased from a sketchy exotic animal dealer, passed the disease on to their new owners in six states. Scientists knew that the virus was similar enough to smallpox that using the same vaccines and treatments contained the spread. That same information is now preventing the spread of the virus in the US and elsewhere. But we still don’t know the source of the misnamed monkeypox virus – its reservoir. We know that monkeys can be infected and pass it on to other animals, including humans, but what animal is infecting monkeys? We won’t know until we go looking.

Research gives us the information we need to prepare for a public health crisis. It also helps us prevent crises by caring for the animals and environment and maybe even eliminate the threats they can pose. To stay ahead of the next outbreak, we need a One Health approach supported by worldwide scientific and medical collaboration – working together for the global good.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Zoonotic Diseases” (2021). Available at: bit.ly/3g0roz6.